Article begins

Author’s note: All the names in this piece are pseudonyms and locations have been withheld.

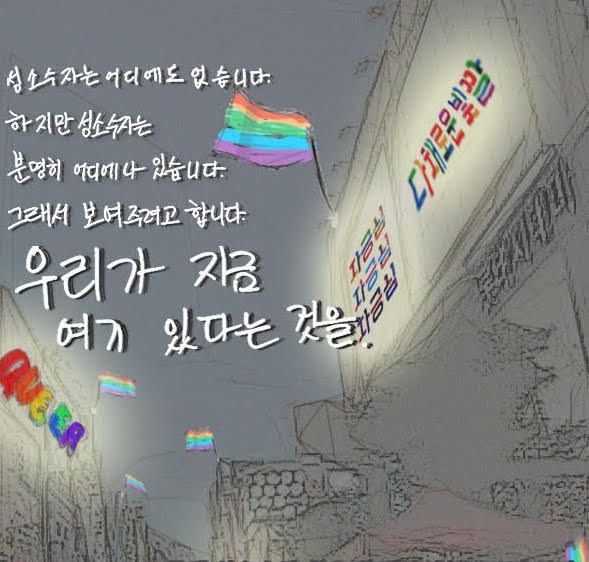

In 2021, I attended a protest held in a bustling shopping district near a local university in South Korea. It was organized by LGBTQ+ student groups and a regional LGBTQ+ advocacy group supported by Korea’s progressive party, Jeong-uidang, to raise public consciousness of LGBTQ+ Koreans’ presence in everyday life and the need for an anti-discrimination law. Some organizers held placards bearing phrases like “The youth want a comprehensive anti-discrimination law!” Others marched the streets, wrapping LGBTQ+ flags around their bodies like capes. We took photos and videos and later uploaded them on social media with #WeAreHere and #StopDiscrimination. The protesters, largely in their twenties, chanted, “We are here!” (우리는 여기 있다!), a phrase often repeated in queer activism in South Korea. To me, it sounded like saying, “We exist!”

But beyond the celebratory colors and phrases, this event was carefully planned and executed to manage the risks activism posed for each protester. The organizers made sure that we recorded ourselves during the protest in case we were refused entry into stores or harassed because of our outfits. Protesters also hid their faces with rainbow-patterned surgical masks during the march. When uploading the recorded footage and photos later online, they censored participants’ faces and altered their voices for anonymity. These measures were taken in response to a well-founded fear of being “outed,” both online and off, which could ultimately cost their social connections and chances for employment.

LGBTQ+ Koreans build politics between a desire for collective visibility and individual invisibility even as the possibility of being “outed” haunts their public and private lives. By selectively concealing and revealing their identities and intentions to others, queer and trans young adults manage to be with and keep a distance from the largely heteronormative public.

Queer life under a heteronormative gaze

Following student activism that helped bring about Korea’s shift from a military dictatorship to a parliamentary democracy in 1987, LGBTQ+ student groups flourished at top universities. Yet compared to the youths who risked their lives to participate in democratization, contemporary Korean young adults are often portrayed as risk-averse, self-interested, and generally indifferent to politics because of economic pressures.

Since economic liberalization following the Asian financial crisis (1997–1998), irregular employment with lower job security, benefits, and income became normalized in South Korea. The brunt of these transformations has disproportionately affected those in their twenties and thirties. A recent report suggests that nearly 40 percent of those in their twenties depend on parents for primary financial support, and over half of unmarried people in their thirties live with their parents.

Yet this narrative of depoliticization is contradicted by young adults’ key role in activism related to the 2014 Sewol Ferry disaster and mass uprisings against government corruption in 2016–2017. Though often unrecognized in public discourse, LGBTQ+ student groups have also been instrumental in the recent groundswell of youth activism in Korea. Over the past decades, queer and trans students have worked to promote anti-discrimination, legislative reform, and destigmatization. Their activities significantly expanded in the mid-2000s, creating groups at more than seventy universities and even cross-university organizations.

Still, as was evident in the protest I attended, students participating in LGBTQ+ activism frequently expressed anxiety over potential harassment and the long-term effects of discrimination. The ubiquity of surveillance in both public spaces and interpersonal relationships have largely contributed to this concern. Like many other countries, in Korea surveillance infrastructure is pervasive and social practices of self-and-other monitoring are a part of daily life. With almost a million security cameras installed by public institutions alone, being recorded in everyday settings is nearly inevitable. People’s daily routes are also logged by banking institutions whenever they use bank cards to pay public transportation fares. The ubiquity of smartphones and social media such as Twitter are also creating a condition for what Brooke Erin Duffy and Ngai Keung Chan call “imagined surveillance”: users’ conscious control over what information they publicize online based on the anticipated scrutiny of peers and employers.

Combined with public homophobia and transphobia, surveillance culture enacts an imagined heteronormative gaze for LGBTQ+ folk—something underscored by regular anti-LGBTQ+ organizing at pride events. At a queer festival hosted in Incheonin 2018, for example, anti-LGBTQ+ protestors from conservative civic groups harassed and physically injured festivalgoers.

They also stoked LGBTQ+ attendee’s fears of being outed by recording them without consent. According to a festival organizer, they taunted, “If you’re proud, then don’t cover your face!” Fears of being surveilled while participating in facets of queer life were further emphasized by the pandemic, as individual privacy was often curtailed to create public safety. In May 2020, state-led contact tracing methods even led to the outing of a twenty-nine-year-old man to his family and employer after his visiting businesses in Itaewon, one of Seoul’s few explicitly queer-friendly neighborhoods.

Although many LGBTQ+ Koreans I met were already out to certain friends, family members, and peers, they frequently worried that mismanaged publicity could jeopardize their employability. Young adults are broadly impacted by economic insecurity, but the situation is more fraught for LGBTQ+ Koreans because there are no enforceable anti-discrimination laws for protection in the workplace—or anywhere else—in society. A 2015 report by the National Human Rights Commission of Korea detailed that 44 percent of LGBTQ+ workers who came out or were outed in the workplace faced discrimination, including pay reductions, exclusion from promotions, or even forced resignations. One college group leader, Yeoungho, clearly summarized this situation when he told me, “Doing activism is burdensome, especially because many of us aren’t economically stable yet. I feel like I won’t be hired if they find out I’ve been doing queer activism. There are so few queer-friendly careers that I can count them on one hand.” For these reasons, many LGBTQ+ interlocutors in their twenties and thirties were particularly concerned that being associated with queer politics could cost their social connections and professional careers.

Between risk and possibility

Under these circumstances of pervasive heteronormative surveillance and a volatile labor market, interlocutors practiced what I conceptualize as a queer politics of “discretion,” in reference to Lilith Mahmud’s definition of the term as “a contextualized set of revealing and concealing practices, of knowing how much to say, to whom, and when.”

For many LGBTQ+ young adults, discretion is a way to stay engaged in collective politics while preserving themselves. One college group leader, Sungwoo, explained various strategies taken to mitigate the risks of being outed in activist and more mundane situations. Group members often don masks and costumes during protestsand commonly use pseudonyms (hwaldong-myeong) when referring to one another. When organizing LGBTQ+ students’ events on campus, the members of Sungwoo’s group would describe their events as “human rights festivals for minorities” to stave off harassment. When confronted by other students, they often claim to be allies—because being a queer ally is more socially acceptable than actually being queer. They also removed the label from their official meeting room door to prevent defacement, rumors, and bullying, making it a kind of open secret. As another group leader, Narei, explained in an interview, “We take a lot of care to secure participants’ anonymity. The primary goal is that everyone ends up safe and that no one is outed. If we let one person get outed, it becomes pointless and contradicts the existence of our group and the purpose of our activism.”

But the outcomes of queer discretion are not always liberatory. Sungwoo confessed, “Finding the balance between activism and the rest of my life is becoming harder as I get closer to graduation, because I actually have to think about my future now.” To practice queer discretion entails the constant anticipation of discrimination, which creates a heavy affective burden of self-regulation—in line with the neoliberal demands of the market and discourses of hetero- and cisnormativity.

When we discussed the future of queer politics in Korea, Yeongho said he was more worried about the people doing activism than the activism itself. He likened this tension to activists “passing a bomb around” (pogtan dolligi) among themselves, not knowing when it would explode. As Sungwoo described, it invites both risk and possibility: “Finding people to do activism is so hard because there’s always a possibility of being outed and experiencing even more economic instability. It’s exhausting. All my friends worry about this. But we have to do it to make ourselves real to the rest of the world.”

Many interlocutors, including Sungwoo, emphasized the significance of cultivating discretionary politics that entailed not just visibility but also invisibility as a means toward both everyday survival and activism. As Naisargi Dave and Cymene Howe have observed, the dominant logic of visibility politics—a belief that more visibility leads to increased tolerance—does not always define queer activism transnationally. On the one hand, queer Koreans’ careful work to ensure each other’s mutual invisibility emphasizes the vulnerability of their subject positions. On the other, it highlights the importance of ethical discretion within queer politics and the very practice of ethnographic research. As my larger work explores, queer discretion exists alongside other semi-public forms of politics, allowing queer and trans interlocutors different political and social possibilities, even as it complicates their existing vulnerabilities. More than just being “out” or “passing” as heterosexual or cisgender, their politics attempt self-preservation while aspiring to build a future of collective recognition and rights for queer and trans Koreans.

Jieun Cho and Aaron Su are contributing editors for the SEAA section in Anthropology News. This piece is part of the SEAA series, “The Future of the ‘Public’ in East Asia.” Contact them at [email protected] and [email protected].